Sustainable tourism examples and considerations 2023. Are you familiar with regenerative tourism?

Have you ever heard of not just sustainable but regenerative tourism?

This year (2023), I wanted to inspire and share valuable information about what is probably the newest and most exciting version of the sustainable approach to tourism.

I am Sara, and on this site, where I welcome you, you will find information on sustainable tourism, accessibility, and solutions to waste. So don’t wait any longer. Read on.

What I found is super interesting, if a bit disappointing. Those who are developing (we’ve been talking about it in theory since 2007) the regenerative tourism approach are doing so because they believe that there is no more hope for the sustainable tourism approach to be carried forward and to be able to become not only mainstream (in Italian mainstream) but also its own best version.

I have read several publications and realized that what I think is correctly sustainable tourism to aim for, to aspire to, is by most of my colleagues now considered the regenerative approach.

On the other hand, I believe that being too rigid in labelling and name/definition changes to evaluate approaches and projects can be counterproductive.

Allowing more flexibility regarding the results achieved by destinations and activities is advisable as this also increases the likelihood of succeeding in achieving an area that will one day no longer need labels to indicate work in progress toward improvement (whether this is in the area of social, environmental or economic responsibility).

Of course, things are not quite that simple, so I decided to share the information I found. Although I have been dealing with sustainability since 2011, I have a reasonably accurate view of the situation also given by fieldwork with both destinations and tour operators and a personal vision that influences it.

I will try to be objective in my descriptions, inserting my comments only when deemed appropriate and only when I can confirm with practical examples my different views.

Apart from that, I am convinced that if the goal remains improvement, we can call the approach and diversify it in 50 different ways; at least we deal with these issues daily and related projects weekly.

Those outside the field may have more confusion and difficulty, mainly when we translate concepts into languages other than the original and which have in their context precise meanings for the terms we use.

In Italian, first and foremost, when we talk about regenerative tourism, we commonly mean from the point of view of guests, and visitors, an experience that can regenerate you (recover from mental or physical fatigue), and generally, we link this kind of experience to physical well-being. However, in recent years there has been more attention to psychological art.

In Italy, there is very little attention and communication dedicated to the destination and the operators, especially if we want to go beyond the economic concepts of profit, market, business models, and revenue.

When we read information about the tourism sector, we find economic terms for operators, statistical terms for arrivals, stays, and spending for destinations, and the duration of the social sphere for nonprofits.

Everything else refers almost exclusively to tourists: needs, expectations, products, and costs.

In Italian, first and foremost, when we talk about regenerative tourism, we commonly mean, from the view of guests and visitors, an experience that can regenerate you (recover from mental or physical fatigue). Generally, we link this kind of experience to physical well-being. However, in recent years there has been more attention to psychological art.

In Italy, there is very little attention and communication dedicated to the destination and the operators, especially if we want to go beyond the economic concepts of profit, market, business models, and revenue. Instead, the standard view is that you have to give tourists what tourists want, so more and more tourists will come (or spend more).

Only small realities and few destinations have or want to integrate the needs of residents into the elements to be considered in the tourism development of a place.

For this reason, the sustainable approach to tourism becomes complex to use. Almost impossible unless working in stages, gradually approaching the needs considered by the most immediate parties and slowly expanding them.

In such a context, to be able to hope to implement a 100 per cent sustainable approach in just a few years is not a forward-looking idea. However, if we add the local culture of slow change and only when mandatory for most activities and even the public sector, we can say that the changes seen in the last ten years are fascinating.

Indeed, the “easiest” change to enforce is related to cost reduction for everyone, from operators to destinations. The difference started with joint interests between the public and private sectors.

Another socioeconomic hybrid change is related to accessibility because while social guilt for excluding specific categories of people because of physical barriers present everywhere has finally produced laws and regulations to curb discrimination, the fact that people with disabilities have good spending potential is helping the private sector to improve, even more than the law requires.

Involvement and consideration of the needs of residents not connected with the sector are much more difficult to justify and consequently implement, except perhaps to respond to specific problems that generate serious complaints and protests not only in one municipality but in several places, such as over-tourism and plastic pollution.

What we can see, however, is a steady growth of interest and sharing of issues and problems that generate everyday situations in different cities (Italian and European). This sharing allows me to report needs and solutions and generate interest in residents who I can, in this way, influence their public sector to do more, to do better.

Without a beginning and a gradual, albeit slow, improvement process, no approach can be successful, especially in Europe, in mature and established destinations that have decades of experience. Of course, this does not mean that another system cannot work here, but it certainly means that not everyone is ready to leave the old way for the new. That’s why covid and 2020 have been so interesting for the sustainable and even regenerative approach.

What do we mean when we talk about regenerative tourism?

Regenerative tourism is a holistic approach that originates in regenerative development. It promotes collaboration and partnerships among all local tourism stakeholders and encourages diversity in regional economic systems to avoid extreme dependence on tourism for a population’s survival. These local populations are included in decision-making processes in an inclusive and equitable space to bring value to communities and respond to the environment and biodiversity of the place (definition found here https://www.hospitalitynet.org/opinion/4114141.html ).

Regenerative tourism understands that visitors and destinations are part of a living system embedded in the natural environment and operate according to the rules and principles of nature.

The main reason for this different and specific view is that sustainable tourism has failed in this. Therefore, one wants to use this “new” concept to emphasise the part on which sustainability has the most difficulty.

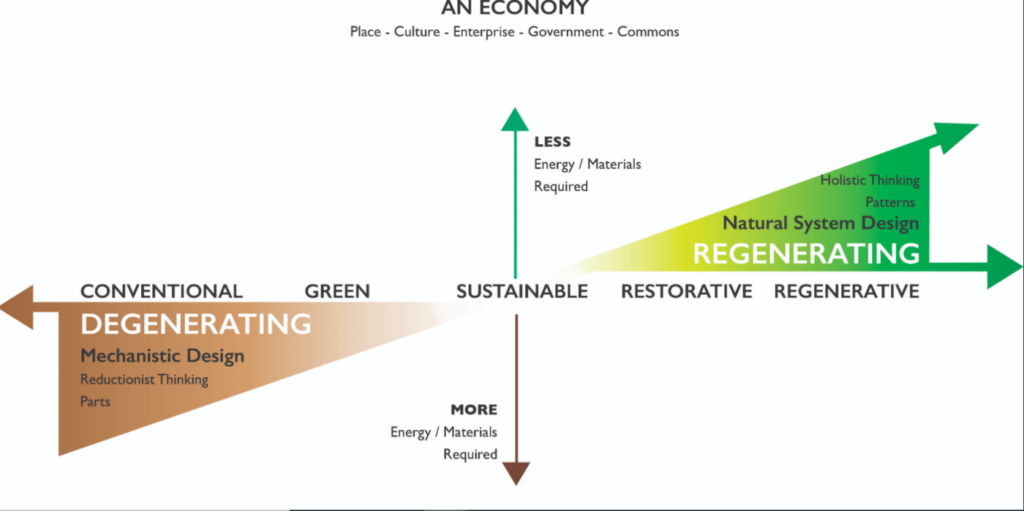

Regenerative design departs from the perception of sustainability in three primary ways.

First, it shifts the frame of reference from minimal impact to positive impact.

Second, it questions human-environment relations based on the Cartesian separation of subject and object.

Third, it seeks to reconnect environmentalism with a socio-political dimension, which has been lacking in much sustainability discourse.

To understand what it means to do regenerative tourism, I thought I would share two examples, two research papers found on academia.edu and written by some of the most exciting researchers.

Ecotourism development in the Torres Strait islands.

The project team comprised architecture students from the University of Melbourne who visited Moa Island to design an ecotourism facility.

This article introduces the concept of regenerative tourism and reflects on developing an architecture that becomes an active part of its context.

The Torres Strait Islands are located between Cape York’s tip and Papua New Guinea’s southern coast. Moa Island is located in the western Torres Strait and is one of 14 islands reserved for island communities (Finch 1977, p.1).

Typically each island has only one community; however, Moa is unique with both Kubin and St Pauls’s communities.

Despite the presence of two communities on Moa, only the Mualgal people of Kubin are considered the traditional owners of the land.

Mualgal of Kubin is considered the traditional land owners, with their ancestors coming from Muralug and living in “seven different villages scattered around the island” (Nawia 1991, p.1). This origin story is markedly different from that of St Pauls, which was established as a reserve by the Queensland government in 1904 following the forced repatriation of Pacific Island workers.

Education is highly valued in the Kubin and St Pauls communities, but facilities are limited. Individual elementary schools teach Moa children up to the seventh grade. From grade seven to 12, local adolescents attend schools on Thursday Island (Capital) or boarding schools in Cairns and Townsville (Occasional Paper 17 2006, p.78-79). Moving adolescents away from Moa for educational reasons is supported and resisted by the older generation.

While education is seen as “the way to improve children’s opportunities,” forced distance between family members and exposure to the West is seen as “causing erosion of traditional culture”(Occasional Paper 17 2006, p.75).

Employment opportunities in Moa are also limited; the result is a problem identified as “population mobility” and is a source of great concern to community elders, who argue that “young men are going to live in the southern mainland and by their going destroy the island’s ability to preserve knowledge inherited from the past” (Lawrie 1970, p. xxii).

The first point of differentiation between sustainability and the concept of regenerative design is that our actions should bring net benefits to our ecological and social environment. The application is more complicated, but it is based on what William Reed described as “building capacity rather than things.”

The net benefits of the ecotourism resort relate to a set of long-term and short-term goals set by the working committee in response to local issues concerning employment, education, population mobility, and culture loss.

The resort aims to increase the employment opportunities available on the island and discourage current emigration patterns.

The absence of adequate educational facilities would prevent the training needed in Moa. As a result of this finding, the group agreed that part of the design process should include a cultural centre that would be a second facility to the ecotourism resort.

In addition to the social and educational benefits of the resort, the facility is expected to add value through the economic empowerment of local people. The working committee identified opportunities for expansion in supplies, entertainment, day trips to nearby islands, fishing, and local crafts.

Celebrating nature is an essential aspect of life in Torres Strait.

During the consultation period, the working committee identified several strong values that contributed to the design of the ecotourism resort. Twelve design principles, nine of which represented the need for the ecotourism resort to work with and enhance the natural environment.

A maximum of five visitors arrive in Moa in the late afternoon to begin a five-day trip. The working group specified the maximum number of visitors as part of its ethos of care, ensuring the quality of the visitor experience while limiting the socio-cultural impact.

Connection/Ecological Footprint: Visitors are greeted by the local guide at the airport and asked to collect their luggage and meet outside the airport to begin the walk to the resort. To encourage greater responsibility on the part of each visitor regarding the amount of “stuff” they bring to Moa, visitors are expected to walk to the resort carrying their bags. It is thus intended to avoid inappropriate attitudes; as tourists, we often have more than we need.

Travel/Diversity: With backpacks on their shoulders, visitors follow their guide outside the airport fence and cross the road to an opening in the vegetation and the beginning of a raised walkway. The raised walkway to the resort is designed to immerse visitors in the natural environment.

Traditional weaving and thatch on a recycled wood structure on concrete logs indicate that the building is intended as a contemporary interpretation rather than a conventional construction.

Including gutters and rainwater tanks, a solar hot water system on the hut, and photovoltaic panels express the building’s self-sufficiency. In addition, the strict visitor program designed by the working group combines a variety of activities to encourage visitors to learn about the local culture and environment.

Regenerative design deals with complex relationships that form an integrated whole.

When considering how a single group of people initially dominated the design process, the working committee aspired to represent community needs and concerns, with each member pursuing a social, economic, political, or environmental agenda.

This approach had several interesting and unexpected consequences.

First, before the arrival of the student group, it seemed that the members of the working committee had not established, as a group, their expectations of what a new structure should achieve.

The different ideas motivating Ben* and Penny* exemplify how regenerative design deals with the complex web of relationships.

Ben focused on income generation, and his ideas were closely aligned with the short-term benefits associated with mass tourism. He sought to promote activities and experiences that could be marketed to high-paying guests. Some of his early suggestions included “tourist/antique stores along the beach…a gazebo, a golf course, tennis courts, a sauna…and a restaurant selling $17 steaks.”

In addition to being contextually inappropriate, her ideas did not consider how the infrastructure could be designed to achieve the experience or its possible environmental impact.

In contrast, Penny* perceived the ecotourism resort as a tool that could be used to address the many social problems regarding employment, education, population mobility, and loss of culture. For her, the facility was an opportunity to create an education and training centre supported by a small-scale tourism enterprise.

However, her ideas did not pay attention to addressing other related issues, such as the possible adverse effects of tourism on culture, management, governance, financing, and human resource management.

Regenerative design is still evolving and maturing in its ideas and applications. Unlike sustainability, it is not based on an idealized endpoint but recognizes the need for a development process along diverse, divergent, and converging paths.

The Moa student group set out to design an ecotourism resort that carefully addressed the “cultural,” sustainability, technical, socio-economic, and environmental aspects important to the people of Moa and Torres Strait.”

Regenerative design work helped in this task by setting realistic goals. The design process can be linked to all three principles.

In the case of the first principle, to be genuinely beneficial to the community, the ecotourism resort had to add value to the lives and prospects of the young people living in Moa by actively involving them.

Second, to be accepted by the community, the ecotourism resort had to have a connection to the place, which in this case meant reflecting the importance attached to Ailan Kastom (island culture).

The design process engaged the community in a narrative describing the articulation of the project through the environment.

Finally, the socio-political aspect of the design process provoked debates. It allowed the different dimensions of difference among various stakeholders to be questioned and negotiated, enriching the proposal.

Stimulating gender equality and regenerative tourism: the case of Karenni Huay Pu Keng village.

This case explores how an “objectifying” form of tourism can be transformed into regenerative tourism, focusing on the case of the Karenni village Huay Pu Keng.

It is the only Karenni village that has converted to community-based tourism (Comunity Based Tourism).

The report describes the results of how it was transformed from a “show village” into a tourism destination based on women’s and men’s capacity building and new relationship building.

Before community-based tourism (CBT), Kayan women, a subgroup of the Karenni, were objectified in the tourism industry because of their distinctive gold-colored neck rings.

After initiating a community tourism process, training was organized with affected community members, particularly women, and their capacity to invest in sustainable tourism activities was developed, providing additional income.

Currently, the positive consequences of this transition to gender equality in Huay Pu Keng are visible.

Both males and females are recognized as having an equal share not only in the financial benefits but also in the provision and management of the tourism experiences themselves. Both are included in tourism developments that have led to equal opportunities in tourism employment and leadership skill development.

For example, they have learned how to welcome tourists, conduct workshops based on their skills, and support other services such as accommodation management. This improved the ability of men and women to be involved in the management and operational activities.

Several villagers shared that both men and women feel empowered in communicating their skills and stories to tourists, which has led to intrinsic motivational factors and positive emotions such as pride and happiness.

Karenni women are no longer looked at as objects, but share their lives and experiences with tourists.

To avoid cultural stereotypes and understand the lives of women in different ethnic groups, storytelling of the Kayan, Kayaw, Pakayor, Red Karen, and Shan of Thailand is shared at the village cultural and tourism center.

Tourism is recognized as valuable to the community because it brings financial benefits to families. In this case of an indigenous community, community tourism has empowered formerly oppressed women and led to greater personal leadership of women.

To ensure inclusive and regenerative tourism, a gender balance in the distribution of tasks, education, income, and leadership is crucial (Andrews et al., 2021).

This aspect is included in the community tourism process and can therefore be considered a participatory tool for the long-term development and regeneration of society. Community tourism can be used as a model for developing gender equality in a tourism destination such as Huay Pu Keng (Nitsch and Louwman-Vogels, 2020).

Community tourism is considered a process of regenerative travel, as it includes reliable and authentic experiences that have a positive impact on both the environment and the local community (Walia, 2021). At the same time, it creates an authentic bond between tourists and locals, stimulating community development, well-being, and social equality (Craig, 2007).

Sara – tourism sector consultant

PS. Do you want to GROW your business with POSITIVE impact… without huge investments? Sign up for the email list by clicking on START HERE!

Or click this link https://www.sustainabletourismworld.com/start-here/ to download my INFOGRAPHIC!